Students in Julie Fydenborg’s English Honors II course concluded a month-long reading of Julia Alvarez’s How the García Girls Lost Their Accents this Friday. Throughout the unit, students were exposed to conversations around the use of banned books and whether texts should be censored in public learning. The unit challenged students to learn about a world outside their own by entering texts that have been banned across the country.

How the García Girls Lost Their Accents tells the story of four sisters who, after immigrating to the United States from the Dominican Republic, grapple with their evolving identities and the clash between their two worlds. Alvarez conveys the journey of the immigrant experience. Through the García sisters’ stories, Alvarez raises the question of defining yourself amid experiences.

Though this is Ms. Frydenborg’s first sophomore honors class, the controversial book is not new to the district. Frydenborg first learned of the book back when she taught it in the old Morgan school as part of her English class. Frydenborg appreciated the text because of its interesting narrative structure of reverse chronological order and decided to take on How the García Girls Lost Their Accents as part of a larger focus on the immigrant experience. “The Garcia girls fit into how I am starting out with sophomore honors, which is to really think about the immigrant experience and what it means to be an American with all the goodness and ugliness that comes along with that,” she stated.

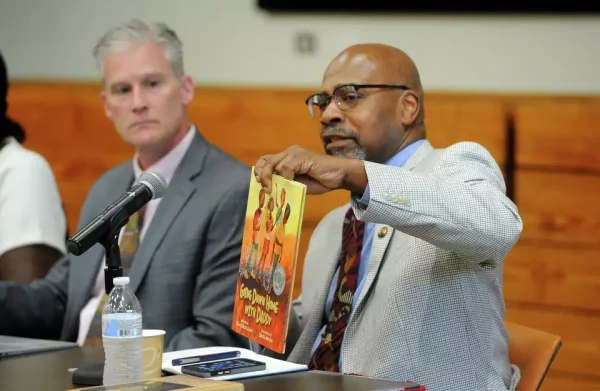

According to the American Library Association, in Connecticut, there have been overall 1,269 demands to censor library books and resources in 2022. Books are often banned for challenging readers to confront issues that may be uncomfortable. For example, Douglas Lord, President of the Connecticut Library Association, says in Westport,

“Gender Queer” and “Let’s Talk About It” are the two most commonly challenged nonfiction titles in Connecticut. How the García Girls Lost Their Accents has faced bans or challenges for its depictions of sexuality, use of language, and critical exploration of power dynamics within and outside the family. Although many of those challenges have justification, the question arose in class: is this censorship or protection? “Banning books is a form of censorship, and I think that if people are censoring knowledge, I don’t trust the reasons behind it,” Frydenborg added.

Despite the challenges posed by book bans, freshman Peyton Vece continues to read banned books. Rather than avoiding the hard topics, students strive to learn how to process them. “I own To Kill a Mockingbird, and it helps me stay educated on controversial topics. I think banning books is not necessary and that it is censorship,” Peyton Vece said.

Students from Julie Frydenborg’s sophomore English Honors II class visited the Ivoryton Playhouse to watch Alabama Story by Kenneth Jones on October 8th. She wanted to show her students how banning affects people and the narrative of history. It shows that in 1959, a segregationist state senator and a tough state librarian fought over the right to read a contentious children’s book about a black bunny marrying a white rabbit as the civil rights movement was gathering steam.

“The government and those people didn’t want people to think it was okay that white people and black people were together, and so it’s just another example of trying to control people’s thinking through banning books,” Frydenborg explained.

While books like How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents by Julia Alvarez may be controversial, teachers such as Ms. Frydenborg think that they are invaluable for the discussions they inspire. By leaving room for open discussion, schools can ensure that students stay informed and are ready to engage in a diverse world